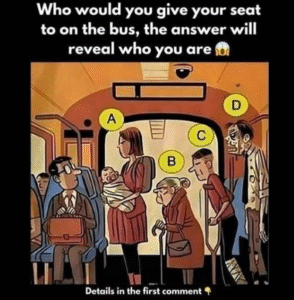

🚌 The Seat We Offer: A Moral Puzzle of Compassion, Identity, and Shared Space

Public spaces often serve as the great equalizer. On a bus, in a subway car, or within any crowded setting, individuals from all walks of life share a confined area, their differences suspended in the rhythm of collective movement. Yet within these shared spaces arise small, seemingly simple choices that expose deeper moral puzzles. Chief among them is the act of offering—or not offering—your seat. At first glance, it looks like a matter of politeness. But in truth, it carries profound implications about compassion, identity, dignity, and our relationship with one another as human beings.

1. The Bus as a Stage of Everyday Ethics

The bus is not just a vehicle; it is a theater where everyday ethics are performed. The seats represent more than places to rest; they are opportunities to express empathy or, alternatively, to reveal indifference. When a young person gives up a seat for an elderly passenger, society nods in approval. When someone fails to do so, disapproval simmers quietly—or erupts loudly, depending on the community.

But what lies beneath this interaction? The act of offering a seat is voluntary, yet also socially expected. It is a courtesy codified not in law but in collective conscience. To refuse is not a crime, but it risks being interpreted as selfishness or moral failure.

2. Compassion in Practice

At its heart, offering a seat embodies compassion. It recognizes that another person might need comfort, safety, or dignity more than oneself. Compassion here is not abstract but practical: the ache in an elderly woman’s knees, the exhaustion of a parent juggling groceries and a toddler, or the discomfort of a pregnant passenger navigating a crowded aisle.

In offering a seat, the giver makes a small sacrifice—momentary discomfort or inconvenience—for the benefit of another. And in this gesture, the bonds of community are reaffirmed. It tells us that even in crowded, impersonal spaces, we remain responsible for one another.

3. The Puzzle of Identity

Yet, the decision to offer a seat also intersects with identity. Imagine a passenger considering whether to offer their seat to a person who appears pregnant, but uncertainty clouds the judgment. Offering could be interpreted as kindness, or as an offensive assumption about someone’s body. Similarly, someone may hesitate to stand for a person who might be elderly, but who may not see themselves as frail.

Here lies the puzzle: kindness often requires recognition of another’s vulnerability, but recognition risks misjudgment. The moral intent can collide with the social meaning. A seat offered in goodwill may be declined in pride or misinterpreted as pity. Thus, identity complicates compassion, reminding us that morality is not only about what we give, but also how it is perceived.

4. The Shared Space of Dignity

Seats are more than objects; they are symbols of dignity in shared space. To be left standing despite visible need can feel like invisibility. Conversely, to be offered a seat can feel like acknowledgment and respect.

But dignity also extends to the giver. A young adult who consistently rises for elders feels part of a moral tradition, while someone who remains seated under watchful eyes may feel ashamed. The seat thus becomes a mirror—reflecting how we are seen by others and how we see ourselves.

Yet dignity must be balanced. If offering a seat turns into patronizing behavior, it strips agency from the recipient. The key is not charity, but solidarity: recognizing that today you might be strong enough to stand, but tomorrow you may be the one in need.

5. The Question of Obligation

Is offering a seat a duty or an act of generosity? Philosophers debate this subtle difference. A duty suggests obligation: something morally required, like paying debts or telling the truth. An act of generosity, meanwhile, is above and beyond—praiseworthy but not demanded.

Society often treats the act as both. We celebrate those who give up their seats, yet we frown at those who don’t. It exists in a gray zone: not legally enforceable, but morally enforced through social expectation. Perhaps the answer lies in seeing it not as obligation or charity, but as reciprocity—a recognition of our shared vulnerability as human beings.

6. Power Dynamics on the Bus

Offering a seat is never just about kindness; it is also about power and hierarchy. Who has the “right” to sit? Who gets to decide? Sometimes the dynamics are clear: priority seating is marked for the disabled, elderly, or pregnant. But in the rest of the bus, norms shift according to cultural context, gender roles, and personal attitudes.

In some cultures, it is almost automatic for younger people to stand for elders. In others, such gestures are rare or even resisted. What seems universally polite in one place might be considered unnecessary or condescending in another. Thus, the seat becomes a microcosm of cultural values, teaching us how communities negotiate respect and responsibility.

7. The Silent Negotiation

On any given bus ride, a silent negotiation unfolds. Eyes glance, hesitate, or dart away. A person weighing whether to stand feels the pressure of watching strangers. The one who might accept the seat wonders whether it implies weakness. Rarely do words accompany this exchange—it is a choreography of subtle signals: a nod, a smile, a grateful “thank you,” or a polite refusal.

This silent negotiation teaches us about empathy beyond language. It shows that even in silence, moral meaning is communicated.

8. Beyond the Bus: A Metaphor for Society

The bus seat is not just a physical object; it is a metaphor for resources in society. Just as there are limited seats on a bus, there are limited resources—jobs, housing, opportunities—in the world. Who yields their share for others? Who clings tightly, fearing scarcity? Offering a seat reflects the broader question of how we distribute comfort, safety, and privilege.

When we give up a seat, we enact on a small scale what societies must do on a large one: balance self-interest with the well-being of others.

9. The Risk of Indifference

Perhaps the greatest danger is not refusing to offer a seat, but becoming indifferent. In many modern cities, passengers bury themselves in phones, headphones, or books, tuning out the shared humanity around them. Compassion requires awareness, but awareness is blunted by distraction. The puzzle then becomes: how do we cultivate attentiveness in environments that encourage detachment?

To notice another’s need is itself an act of moral perception. Without it, the opportunity for compassion vanishes before the thought even arises.

10. Toward a Philosophy of Shared Space

The seat we offer—or refuse—captures the tension between self and other, between autonomy and responsibility. It teaches us that morality does not only emerge in grand gestures, but in the small decisions of everyday life. Each bus ride becomes a lesson in how to live together: not as isolated individuals, but as companions in a shared journey.

The puzzle is not solved by rigid rules, but by cultivating virtues: compassion, attentiveness, humility, and respect. In practicing these, the seat becomes not just a cushion of comfort, but a token of humanity.

Conclusion

“The Seat We Offer” is never just about seating arrangements. It is about who we are when faced with the needs of others in the fleeting intersections of daily life. On the bus, the train, or anywhere shared space exists, the seat becomes a moral puzzle—challenging us to weigh compassion against pride, obligation against generosity, and dignity against dependence.

In the end, the true measure of a society is not how its people act in extraordinary crises, but how they behave in the ordinary moments—when one person, tired yet aware, quietly rises to offer a seat to another.