A new and deeply disturbing simulation has revealed just how much microplastic the average person consumes every week—and the findings are nothing short of terrifying. Microplastics, tiny particles less than five millimeters in diameter, have infiltrated nearly every aspect of modern life. From the food we eat to the water we drink and the air we breathe, these minuscule fragments of plastic are now an unavoidable part of our environment—and, alarmingly, our bodies.

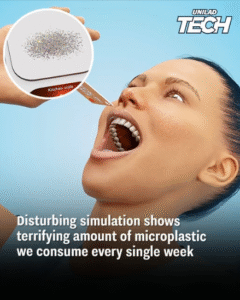

The simulation, created by environmental researchers using data from global studies, aims to provide a visual and physical understanding of microplastic ingestion. In the demonstration, a week’s worth of human microplastic consumption is represented by a small plastic credit card, weighing roughly five grams. That’s right: we are potentially ingesting the equivalent of one credit card per week through our daily lives.

The sources of this plastic exposure are everywhere. Bottled water has been shown to contain significantly high levels of microplastic particles. Even tap water, long considered safer, isn’t immune—especially in areas where old plumbing systems may leach plastics. Seafood, particularly shellfish like mussels and oysters, are also culprits. These creatures filter ocean water to feed, and in doing so, they accumulate plastic particles in their tissues—particles that we then consume.

But it doesn’t stop with water and seafood. Microplastics are present in table salt, beer, fruits, vegetables, and even the dust that collects on your furniture. Inhalation is another pathway. Indoor environments, especially those with synthetic furnishings and carpets, release plastic fibers into the air, which settle in our lungs when we breathe. The average person inhales thousands of microplastic particles annually.

Scientists are still uncovering the health impacts of microplastic ingestion and inhalation, but early research is concerning. Once inside the human body, these plastic fragments can become lodged in organs or pass into the bloodstream. Some plastics contain toxic additives, such as phthalates and bisphenol A (BPA), which are known endocrine disruptors and have been linked to a range of health problems including hormone imbalance, fertility issues, immune system suppression, and even cancer.

The simulation also explores the cumulative effect of long-term exposure. Over a year, the average human might consume more than 250 grams of plastic—more than a large bowl of rice. Over a lifetime, this adds up to over 20 kilograms, or roughly 44 pounds of plastic inside our bodies.

To emphasize the gravity of the situation, the researchers placed the weekly amount of plastic next to everyday objects for scale. Seeing a credit card next to a plate of food, with the message “You may be eating this much plastic every week,” forces a visceral response. It’s no longer an abstract problem; it’s one that’s happening in our bodies right now.

Environmental activists and scientists hope this simulation will serve as a wake-up call to both the public and policymakers. The rapid proliferation of single-use plastics, the breakdown of larger plastic items in the environment, and the inadequate waste management systems worldwide are contributing to this crisis. The oceans, already overwhelmed by plastic waste, continue to degrade larger plastics into smaller and smaller pieces, which are then consumed by marine life and cycle back to us.

Some of the microplastics come from surprising sources. Synthetic clothing, for example, sheds microfibers when washed. These fibers are too small to be filtered out by water treatment plants and end up in rivers, lakes, and oceans. Every time we wash a polyester shirt or fleece jacket, we are unknowingly adding more microplastics to the environment.

Even personal care products, such as exfoliating facial scrubs and toothpaste, have historically contained microbeads—tiny plastic particles intended to scrub and polish. While bans have been enacted in some countries, these products continue to be used and sold in many parts of the world.

Efforts to address the problem are growing, but not fast enough. Some countries have implemented bans on certain single-use plastics, while others are investing in biodegradable alternatives. Companies are being pushed to reduce plastic packaging and to develop closed-loop recycling systems. However, many environmental experts argue that without global coordination and aggressive policy changes, these efforts will fall short.

Public health organizations are also calling for more research into the long-term effects of microplastic exposure on human health. Right now, the full extent of the impact is unknown, but evidence is mounting that this invisible form of pollution is harming not just the planet but also the very people who inhabit it.

The simulation closes with a stark message: microplastics are now so ubiquitous that avoiding them entirely is nearly impossible. Still, individuals can take steps to reduce exposure. Drinking filtered tap water instead of bottled water, avoiding plastic-packaged foods, choosing natural fiber clothing, and reducing reliance on synthetic products can help. But individual action alone is not enough—the real solution must come from large-scale changes in how plastic is produced, used, and disposed of.

In the end, this simulation does more than inform—it shocks, confronts, and demands reflection. It asks a chilling question: how much plastic will be enough before we act? As researchers and campaigners continue to ring alarm bells, the disturbing truth remains clear—microplastics are inside us all, and their impact may be far greater than we ever imagined.