The Sozopol “Vampire”: Bound by Iron and Fear

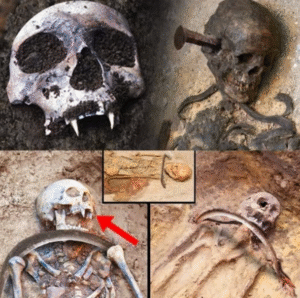

Few discoveries capture the public imagination quite like the macabre. In 2012, in the coastal town of Sozopol, Bulgaria, archaeologists unearthed a skeleton that seemed ripped from folklore. Its chest was pinned by an iron rod, its body buried with peculiar care meant not to honor, but to restrain. Locals and journalists quickly dubbed it the Sozopol Vampire.

Though centuries old, the skeleton stirred global headlines, tapping into humanity’s timeless fascination with vampires, curses, and the blurred line between myth and reality. But behind the sensationalism lies a story of fear, belief, and the ways societies protect themselves from the shadows that haunt their imagination.

Unearthing the Undead

Excavations in Sozopol were routine at first. Archaeologists dug through layers of the ancient Black Sea settlement, uncovering churches, streets, and ordinary burials. But then, in one grave, they encountered something unusual.

The skeleton was not laid to rest peacefully. A heavy iron stake pierced through its ribcage. Its teeth and bones suggested it belonged to a man, possibly in his 40s or 50s, who lived during the Middle Ages. More shocking, the bones bore signs that they were deliberately nailed down, ensuring the body could not rise.

To archaeologists, the meaning was clear: this was an “anti-vampire” burial, a practice documented across Eastern Europe. The dead man had been feared by his community, suspected of being capable of returning from the grave to harm the living.

Fear That Outlives Death

Why would villagers treat a corpse in such a gruesome way? The answer lies in medieval superstition. Death was not always seen as final. Across Europe, stories told of the restless dead — people who returned as revenants, ghouls, or vampires, feeding on livestock, spreading disease, or terrifying their neighbors.

When unexplained deaths occurred — epidemics, famine, or sudden illness — communities sought someone to blame. Often, suspicion fell on those who had lived on the margins: outcasts, misfits, or feared individuals. If their death did not put an end to the unease, villagers took measures to ensure the corpse stayed buried.

In Sozopol, the iron spike through the heart (or chest) was one such measure. By binding the body with iron, people believed they were pinning down the spirit itself, trapping it in the grave.

The Vampire Archetype

Though Bram Stoker’s Dracula popularized the vampire in modern imagination, the idea long predates Gothic literature. Folklore from the Balkans is particularly rich with tales of the vampir, a reanimated corpse that fed on blood or life-force. Unlike Stoker’s elegant count, these vampires were grotesque, bloated, and terrifyingly ordinary — neighbors who had risen from their coffins.

The Sozopol skeleton fit squarely into this cultural landscape. Local historians suggest that medieval Bulgarians often drove spikes through corpses suspected of vampirism. Other burials across Eastern Europe reveal similar “preventive” rituals: decapitation, stones placed in the mouth, or limbs bound with chains.

The discovery was not unique, but it was chillingly vivid — a reminder that vampire legends were not just campfire stories, but real fears acted out upon real bodies.

The Identity of the Sozopol “Vampire”

Who was this man, bound by iron and remembered in terror? Archaeologists cannot say for certain. Some suggest he may have been a local nobleman, priest, or even a feared criminal. His burial was not hasty; it was deliberate, as if the community gathered to perform a ritual.

One theory posits that he was a heretic or someone accused of practicing forbidden magic. Others think he may have been a wealthy townsman whose eccentric behavior sparked rumors after death. Whatever the case, the extreme burial shows the community felt threatened enough to deny him a normal passage into the afterlife.

Science Meets Superstition

From a modern perspective, the iron stake can be explained without invoking real vampires. Medical historians argue that epidemics of plague and cholera fueled belief in the undead. When villagers opened graves during outbreaks, they sometimes found bodies that appeared “fresh,” with blood at the mouth — a natural result of decomposition. To frightened eyes, it looked like proof the dead were feeding.

Thus, vampire burials became a kind of medieval “public health” ritual. By mutilating the corpse, people reassured themselves they had neutralized the threat. Fear was transformed into action, giving the community a sense of control in a chaotic world.

From Folklore to Headlines

When the Sozopol skeleton was unveiled, global media pounced. Headlines screamed about “real vampires” discovered on the Black Sea coast. Tourists flocked to Sozopol, eager to see the town of the undead. Museums curated exhibits around the find, displaying iron stakes and photos of the grave.

Yet for locals, the story struck a different chord. Many elderly Bulgarians remembered tales of vampiri told by grandparents. The skeleton was not just a curiosity — it was validation that their folklore had deep roots.

The Symbolism of the Iron

Iron itself carried symbolic weight. In many cultures, iron was seen as a protective material, strong enough to ward off spirits and demons. Weapons, nails, or rods of iron were commonly placed in graves of the “restless.” The Sozopol man’s chest stake was not just a practical measure; it was a magical safeguard.

Bound by iron, he was meant to remain powerless forever. Yet in being discovered, he has achieved a strange immortality — not as a predator of the living, but as a cultural icon reminding us of how fear shapes ritual.

The Broader Pattern of “Vampire” Graves

The Sozopol find is part of a wider archaeological pattern. In Poland, skeletons with sickles across their throats have been uncovered. In Italy, a woman’s body was found with a brick forced into her mouth — to prevent her from “feeding.” In Slovakia and Greece, decapitated skeletons point to similar rituals.

Together, these graves paint a map of Europe’s dark imagination. Across regions and centuries, communities took physical, violent measures to bind their fears into the earth. The “undead” were not cinematic monsters, but scapegoats of real anxieties.

What the “Vampire” Teaches Us

The Sozopol skeleton is more than a curiosity for tourists. It is a window into the psychology of fear. Humans, confronted with death and disease, have always sought explanations. When science was absent, superstition filled the gap. Rituals like vampire burials gave people a sense of safety, even if it meant desecrating a neighbor’s remains.

At the same time, the skeleton challenges us to reflect on how communities treat outsiders. The man pinned beneath iron was likely different in some way — socially, physically, or behaviorally. His fate shows how fear of “the other” can outlast life itself.

Closing Reflections

The Sozopol “Vampire,” bound by iron and buried under centuries of silence, is not a monster from legend but a mirror of human anxiety. His discovery reminds us that belief in the supernatural was once practical, shaping how people coped with sickness, death, and uncertainty.

Today, we see him not as a threat but as a bridge between folklore and history. His iron-bound bones whisper of a time when fear ruled the night, when villagers hammered metal through the dead in hopes of peace. And though he never rose from the grave, his story has risen from obscurity, binding us not with fear, but with fascination.