The Truth Behind the Viral Photo of Tourists Posing on Chernobyl’s Radioactive Claw

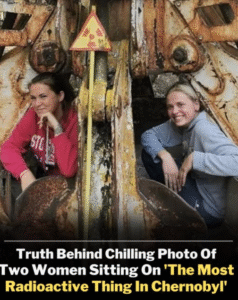

It’s the kind of image that makes you stop scrolling: a group of tourists, beaming at the camera, casually draping themselves across a massive, rust-covered piece of machinery deep within the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. The claw-shaped crane attachment, suspended in history like a relic from a dystopian future, is infamous among nuclear historians. Known simply as “the Claw,” it is one of the most radioactive objects left in the zone.

So when the photo of tourists sitting atop it recently went viral, the internet lit up with outrage, fascination, and confusion. Why would anyone pose on something so dangerous? Was it staged? And just how hazardous is the claw today?

To answer those questions, we have to go back nearly four decades to the disaster itself.

The Night That Changed the World

On April 26, 1986, Reactor 4 at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded during a late-night safety test gone wrong. The blast tore open the reactor core, spewing radioactive isotopes into the air, contaminating vast areas of Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia.

The cleanup, known as the liquidator effort, was one of the most dangerous human operations in history. Soldiers, scientists, and workers were ordered to contain the meltdown using whatever means available. Helicopters dropped sand, lead, and boron into the reactor. Others demolished radioactive debris by hand, wearing little more than cloth masks for protection.

Among the equipment pressed into service was the claw: a massive, heavy-duty crane attachment used to move pieces of reactor graphite, twisted metal, and concrete from the site of the explosion.

The Claw’s Terrifying Legacy

The claw did its job—but at an unimaginable cost. By directly handling chunks of reactor fuel and debris, it absorbed some of the highest levels of radiation measured at the site. Scientists estimate that for years, it was “hot” enough to deliver a lethal dose to a human in minutes.

The claw was eventually abandoned in a yard near the plant, dumped along with contaminated trucks and machinery. Unlike other equipment that was buried or removed, it remained in place, a silent witness to the disaster. Over time, it became one of the most notorious relics of Chernobyl.

For decades, guides warned visitors never to approach it. Even standing nearby could register dangerously high readings on a Geiger counter.

Tourism and the Rise of Chernobyl Voyeurism

By the 2000s, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone had become a strange and eerie tourist destination. In 2011, the Ukrainian government officially opened the area to controlled visits, allowing people to walk through abandoned towns, stand before the ruins of the reactor, and glimpse the consequences of nuclear catastrophe.

The claw became one of the dark highlights of such tours. Visitors could spot it behind caution tape or from a safe distance, while guides told its chilling story. Its presence was a reminder of the invisible danger still lurking, even as wildlife returned and plants grew wild around Pripyat’s silent streets.

The 2019 HBO miniseries Chernobyl supercharged interest in the site, leading to a surge of tourism. Social media influencers flocked there, posing in abandoned buildings or donning dramatic gas masks. Inevitably, the claw became an irresistible backdrop.

The Viral Photo

The most recent viral image of tourists posing on the claw struck a nerve for several reasons. First, it seemed reckless. Even though radiation levels in the zone have decreased significantly in the decades since the disaster, the claw remains one of the most contaminated objects left in the open air.

Second, the photo felt disrespectful. Survivors, liquidators, and families of those who died from radiation exposure see the claw as more than a curiosity—it’s a tombstone of sorts, a symbol of sacrifice and tragedy. Posing on it with smiles and peace signs, critics argued, trivializes the pain attached to its history.

Finally, there was genuine confusion. Was it even safe to sit on the claw in 2025? Or was this photo proof of careless tourism gone too far?

How Dangerous Is It Today?

Experts note that while radiation levels in the Exclusion Zone have dropped due to decay and environmental absorption, certain hotspots remain highly dangerous. The claw is one of them.

Measurements taken in the 2010s showed radiation levels on its surface many times higher than background levels elsewhere in the zone. Standing a few feet away may not pose an immediate risk for a short time, but sitting directly on it—especially for minutes at a time—could expose someone to radiation significantly above safe limits.

To make matters worse, the danger isn’t always immediate. Radiation exposure increases lifetime cancer risk, and its effects may not manifest for years. That’s why even seemingly brief, harmless encounters with contaminated objects can carry consequences later in life.

The Ethics of Disaster Tourism

The viral photo reignited debates about the ethics of “dark tourism,” the practice of visiting sites associated with death, tragedy, and disaster. While some argue that such tourism educates and memorializes, others see it as voyeuristic or exploitative.

At Chernobyl, this tension is especially pronounced. Visitors walk through a place where people once lived ordinary lives—schools with abandoned textbooks, homes with children’s toys, amusement parks that never opened because the disaster struck days before.

When tourists turn those spaces into backdrops for Instagram selfies, it risks erasing the humanity of the tragedy. The claw, in particular, is not just metal; it’s an artifact steeped in pain and sacrifice.

Why People Do It Anyway

So why pose on the claw despite the risks and controversies? Sociologists suggest a mix of thrill-seeking, social media validation, and the human urge to conquer fear. For many, the claw represents danger itself—a radioactive beast tamed by the chance to sit on it and smile for the camera.

Others may not fully understand the risks. Tour guides vary in how strictly they enforce rules, and not all visitors grasp the invisible threat of radiation, which cannot be seen, felt, or smelled. To the uninformed, it may look like nothing more than rusty scrap metal.

Conclusion: The Claw as Symbol

The viral photo may fade from the internet soon, but the claw will remain—rusting, dangerous, and symbolic. It is a reminder of the disaster’s invisible legacy, a monument to both human hubris and human sacrifice.

For some, it is an object of fascination. For others, a relic of grief. But for all, it demands respect.

The truth is simple: the tourists in the photo may have walked away with nothing more than likes and comments, but the claw itself still carries a deadly history. It should not be treated as a playground prop, no matter how tempting the shot may be.

In the shadow of Chernobyl, laughter and selfies may feel like defiance. But perhaps the most powerful way to honor the past is not to climb on the claw—but to stand before it, silent, remembering.